The Making of Thamesmead

Marshland and Masterplans

The story of the construction of Thamesmead starts with the driving in of the first pile into the marshland of Belvedere and Erith in 1967 amidst the bold ambitions for a modern town made of modern materials. Work began on the development of the New Town, the Masterplan for which harnessed the challenges of the watery conditions and open expansive space as key to its design. However, to build on the floodplain foundations had to be very deep, and before any work above ground could be advanced, piling began. An incredible 40,000 piles were used in the first phases of Thamesmead.

The first pile is driven into marshland by Anthony Greenwood Minister for Housing in 1967.

The noise was horrendous. All you had was boom, boom, boom, for hours and hours and hours on end.

More from Doris can be heard in this oral history recording. She talks about the work that had to be done on the heavily contaminated site before construction could begin.

The Contractor

Cubitts (Holland Hannen & Cubitts), who had finished the iconic Royal Festival Hall in 1951 and New Zealand House in 1963, were appointed as the building contractor for Thamesmead. Their proposal was to use a French concrete panel system called Balency and Schuhl. This system used precast concrete wall panels which incorporated service elements such as piping and ducting and thus allowed for the quick and efficient construction of dwellings. Component parts were manufactured onsite and then lifted into position. This approach led to the concrete forms that have become synonymous with images of Thamesmead today.

Cubitts logo can be clearly seen on entry to the site. The panel system can be seen with cranes used to lower them into position.

Balency and Schuhl

In order to realise this panel system — there were hundreds of different types of concrete component needed — an onsite factory was created. The factory, often referenced in reports as the IBF, or Industrialised Building Factory, located in West Thamesmead was one of the first buildings to be constructed in 1967 and was to produce all the necessary pieces for the plans. The hot concrete was poured into the giant moulds and left to cure before being lifted by crane through the factory roof and then transported around the site.

The entrance to the concrete factory

Whole rooms went flying through the air and were slotted in, so that was very exciting watching that from the office window.

Photograph of fabrication of concrete parts in factory within Thamesmead

A B&W photograph of the interior of concrete fabrication factory situated on the corner of Eastern Way and Nathan Way. The GLC constructed a 86,0000 sq ft factory to fabricate and produce the concrete units for use in constructing upto 850 dwellings a year.

Photograph of fabrication of concrete parts in factory within Thamesmead

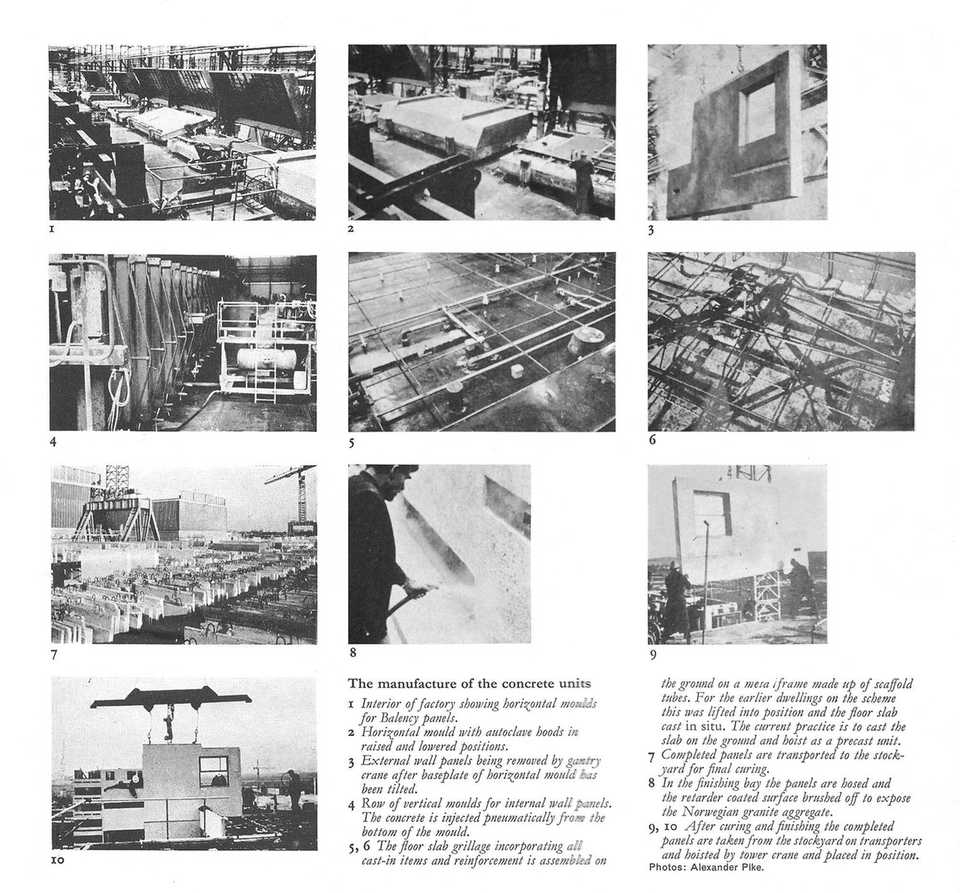

Manufacturing Concrete Units

A photographic sequence detailing the stages involved in manufacturing concrete units in ‘Thamesmead Report’ Architectural Design, November 1969

A photographic sequence detailing the stages involved in manufacturing concrete units in ‘Thamesmead Report’ Architecutal Design, November 1969

Living on a building site

By April 1967, 1494 homes were being constructed in the first phase of Thamesmead. In July 1968, while still a muddy and incomplete construction site, the first family moved into Coralline Walk. While the Gooch family’s maisonette had been carefully checked by the contractor the other dwellings had begun to leak. No more families were to move in until the end of that year.

The Tavy Bridge and Pyramid Club can be clearly seen in this image. The Gooch family moved in while the site was still being constructed.

The trouble with Balency

In a GLC published report from 1976 issues with the system are highlighted. The reference is made to ‘rationalised traditional methods’ of construction being ‘clad externally with panels…of almost identical composition’. In other words the units were cold cast outside the factory on site and made to look like the Balency system. In part this is attributed to sequencing with construction needing to be advanced and partly ‘because of the complex form of the building.’ As it transpired the panels leaked and didn’t work for three story dwellings. Balency wasn’t quite the construction solution it was billed to be. To compound the issue in 1969 the introduction of the Housing Cost Yardstick by the Ministry of Housing forced economies to be made. As a consequence much of Stage 2 lost its distinctive design features and construction began to fall behind.

‘The First Areas’ booklet, published by the GLC in 1976. The booklet shows plans and pictures for Areas I, II and III and gives detail about their construction.

Financial restrains, which resulted in the introduction of the then Ministry of Housing Cost Yardstick for local authority housing in 1969, made it necessary for economies to be exerted in the general form of buildings and their services.

The Three Day Week — Construction Slows

Despite the system chosen for speed and ambitions for the completion of the development, in 1973 the three-day-week meant that construction work slowed considerably. Just 400 homes a year being completed by the end of the decade. Additionally, building in concrete was falling out of favour by the mid 70’s a wider changes — such as the raising of the Thames riverbank to prevent flooding meant that design rules around ground-level buildings were relaxed, changing one of the critical design considerations. The concrete forms of the early construction would be abandoned for more traditional building methods such as brick that feature in the construction of Area 3 (the Moorings) and in later stages in Thamesmead construction.

Arnott Close, the Moorings, in Area 3. By this time the concrete system of Areas 1 and 2 had been abandoned for more traditional building methods